0115 964 7740 - law@curtisparkinson.com

Assessing Testamentary Capacity

3 November, 2021 6 minutes reading time

For solicitors and Will writers, one of the most important parts of drawing up a Will is assessing a client’s fitness to make their Will, known as their ‘testamentary capacity. If the client is elderly or ill or doubts their capacity, how a practitioner establishes this is very important. Since the ’70s, it’s become best practice to assess a person’s capacity by obtaining an assessment from a medical practitioner. This process is known as applying the ‘Golden Rule’.

With more than a quarter of UK residents projected to be +65 or over within the next 50 years, this is statistically more relevant than ever. After all, such Wills are more at risk of being challenged by those disinherited under them.

So how do practitioners test mental capacity, and why is the so-called ‘Golden Rule’ still important?

1. Banks v Goodfellow Test (1870)

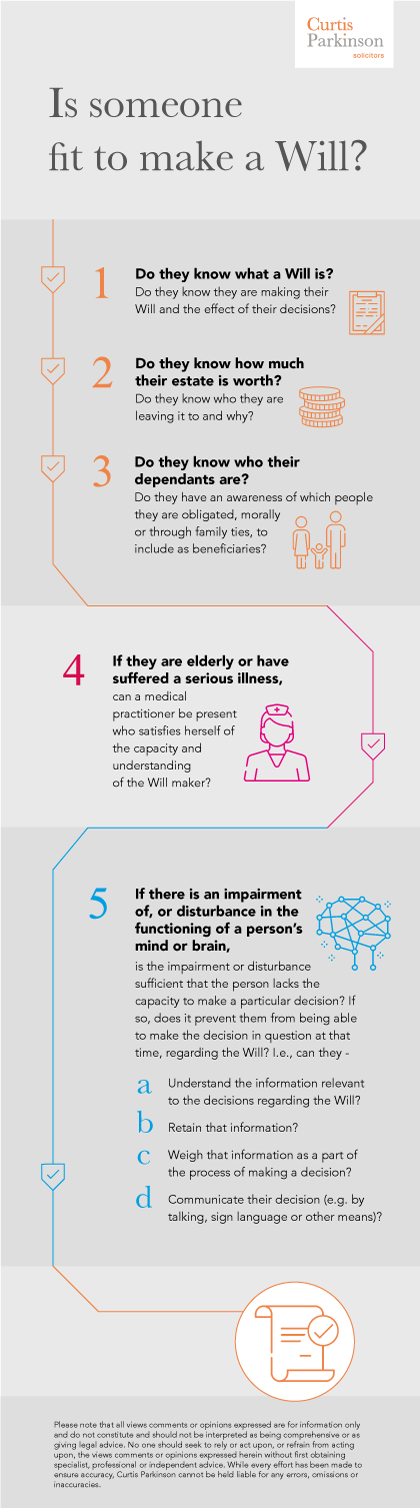

For almost 150 years, the test for mental capacity when making a Will rested with the legal principles established in Banks v Goodfellow (1870). Essentially, this means for any Will to be valid, the person who is making the Will (known as the ‘testator’) must:

- Know what a Will is; that they are making their Will and the effect of their decisions;

- Know how much their estate is worth; to whom they are bequeathing it and why;

- Know who their dependants are; and be aware of which people they are obligated, morally or through family ties, to include as beneficiaries of their Will. Significantly, this provision can be complicated in cases where the testator’s memory is compromised, for example, by dementia.

2. The Golden Rule (1975)

This ‘rule’ was first established in Kenwood v Adams [1975] CLY 3591 and later confirmed in Re Simpson [1977] 121 SJ 224. Both cases were concerned with the doubt surrounding the testator’s ability to execute a valid Will.

Known as the ‘Golden Rule’, Mr Justice Templeman stated that:

“In the case of an aged testator or a testator who has suffered a serious illness, there is one golden rule which should always be observed; however, straightforward matters may appear, and however difficult or tactless it may be to suggest that precautions be taken: the making of a will by such a testator ought to be witnessed or approved by a medical practitioner who satisfies himself of the capacity and understanding of the testator, and records and preserves his examination and finding”.

It’s generally accepted that observing the ‘Golden Rule’ is best practice. However, it is not a rule of law.

3. The Mental Capacity Act (2005)

So, where does The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) fit in?

The MCA introduced a new test for testamentary capacity in 2005.

This legislation was designed to empower and protect those who cannot decide for themselves.

So, for Wills made after 1 October 2007, practitioners must consider the implications of the MCA and the functional tests the Act introduced.

Fundamentally, the MCA follows three guiding principles you must:

- Start with the assumption that the individual can make the decisions;

- Be able to demonstrate you have made every effort to support the individual to decide for themselves;

- Remember that if a person makes a decision that you consider eccentric or unwise, this does not necessarily mean that the person cannot make the decision.

MCA Two-stage Test

A vital element of the Act is the test of capacity, and there are two elements to this assessment:

Stage One

Is there an impairment or disturbance in a person’s mind or brain? If so, is the impairment or disturbance sufficient for the person not to make a particular decision?

If the first stage of the capacity test is met, the second test requires the individual to show that the impairment or disturbance of the brain or mind prevents them from deciding at that time.

Stage Two – Functional Test

Stage two is a functional test focusing on how the person makes the decision rather than the outcome or consequence of the decision.

- To understand the information relevant to the decision;

- To retain that information;

- To weigh that information as a part of the process of making a decision;

- To communicate his/her decision (whether by talking, using sign language or any other means)

This test must be complete and recorded; the documentation must demonstrate the above process.

The Importance of Case Law

After the MCA’s introduction, best practice dictated using the MCA test with the Banks v Goodfellow test, not replacing it.

However, following several high-profile cases, the precise legal position was unclear. Until Walker and another -v- Badmin and others [2014]. In this case, the two daughters of the deceased claimed that their mother lacked capacity at the time she executed her Will. Under the terms of the Will, the deceased left her share of former matrimonial assets on trust to her partner of two years (who was 23 years her junior) for life and thereafter in equal shares to her daughters. Consequently, her estate’s remaining assets were split: 50% to her partner and 25% to each daughter.

In his ruling, Judge Nicholas Strauss QC considered the tests for capacity in Banks v Goodfellow and the MCA 2005. He concluded that although the tests overlapped and would often produce the same result, that would not always be the case, and he, therefore held that the common law test in Banks v Goodfellow still applies.

In James v James [2018] EWHC 43 (Ch) a claim arose following the death of Charles James on 27 August 2012. It concerned a proprietary estoppel claim and a challenge to the deceased’s Will due to lack of testamentary capacity.

Again, this case highlights that judicial views are hardening on the need to obtain a medical opinion for aged testators, almost as a default option. Furthermore, practitioners face criticism if they fail to get medical advice, even if they believe their client to be ‘of sound mind’.

How Can We Make Sure We Do Things Correctly?

It’s easy to be confused by the legislation, new and old. Moreover, subsequent case law has, as we’ve outlined above, challenged accepted practice.

Recommended Approach

In situations where the testator’s capacity may be questioned, every effort should be made not to discriminate. This is achieved by:

- Invoking the ‘Golden Rule’, as described above;

- Making observations as described in the Banks v Goodfellow test: and

- Obtaining medical evidence.

By adopting this approach, the practitioner will be protecting the testator’s interests and their beneficiaries under their Will from a future challenge as far as they feasibly can.

The Doctor’s Role

A medical practitioner should witness or approve the Will to ensure they are satisfied that the testator understands and can make a Will. The practitioner should also document and retain their examination and findings. (Kenward v Adams ChD 29 November 1975)

Uncomfortable (but essential) Conversation

It is challenging to suggest that an older person requires a doctor to check their capacity before making their Will. But, legally, it is vital. Even with a medical opinion, someone could still challenge the Will, but claimants will have a much weaker case if relevant medical evidence exists.

Further Information

We have many years of experience in dealing with sensitive issues such as this. However, we recommend speaking to us in person, so please contact us to arrange an appointment.

Please note that all views, comments or opinions expressed are for information only and do not constitute and should not be interpreted as being comprehensive or as giving legal advice. No one should seek to rely or act upon, or refrain from acting upon, the views, comments or opinions expressed herein without first obtaining specialist, professional or independent advice. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, Curtis Parkinson cannot be held liable for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies.